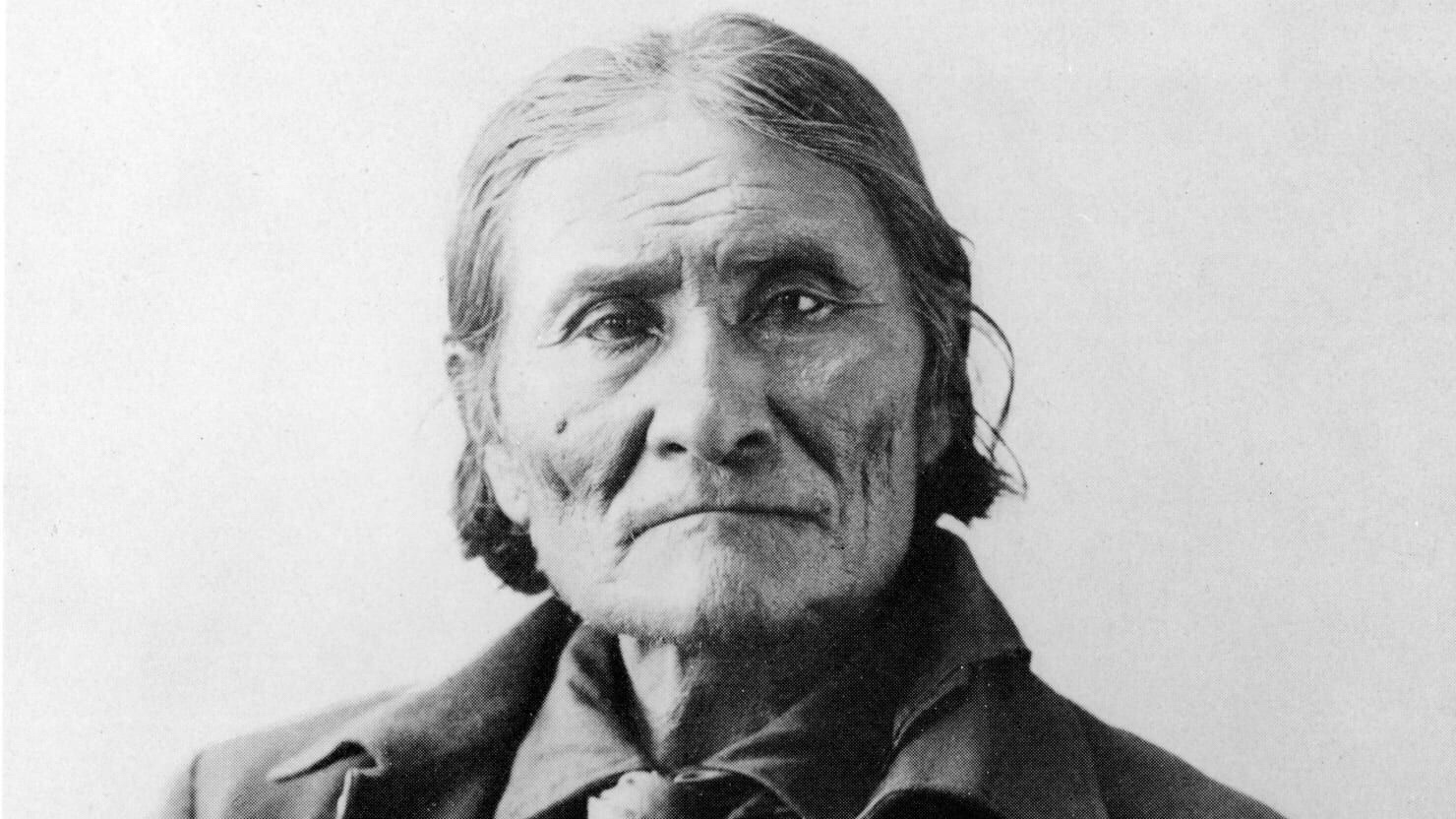

Government is, in most cases, a force for violence and death. Those within the established order claim that those who oppose them are evil or cause chaos. It is known that one of the worst examples of the destructive nature of government is it’s treatment of the Native American population. The image of the atrocities performed against my ancestors in the Cherokee Nation is contained in history books. Everyone knows the story of the forced migration of those people called “The Trail of Tears.” In movies, and other pop cultural references, one tribe still is pictured as vicious killers and enemies of the white man. That tribe is the Apache of the south west. The leader of that tribe just over a hundred years ago was a man named Geronimo. My hope is that by the end of this article, you, like I have, will set aside the propaganda and realize that this man was not the savage you have been taught he was. Geronimo was a victim of the planned eradication of an entire people by both the Mexican and United States governments. It is time to bring his fight to a new century and learn from this forgotten freedom fighter. We should adopt his strength of character and cry out to the world that his tragic story will not happen to our families.

The majority of the information in this post comes from one source. That source is the autobiography of Geronimo. I feel that it is important that this story is started as the man who transcribed it, S.M. Barrette, started that book. In the introduction of the autobiography, Barrette describes the many hurdles placed by the U.S. government to the publication of the book.

Initially, Barrette went to the commanding officers who were holding the Apache prisoners of war, including Geronimo, for permission to publish the story of his life. That’s right, he was held as a prisoner of war in Oklahoma. The response to his request was a flat denial. The officer added that not only should Geronimo’s story not be told but that he, “should be killed.” Let me be clear, at this time the old Apache was 76.

Barrette was not detoured. He eventually got the go ahead from the president at the time, Theodore Roosevelt, to publish. This led to Geronimo dedicating the book to Roosevelt. Still the president, being a statist, was not just going to let anything be published. He instructed that the manuscript first be approved by the Department of War. We should keep in mind that this is what made it past the government censors.

The beginning of the process to get it to print started in 1904 and did not finally get approved, until July 1906, taking over 2 years. Also, to be clear of why it took so long, it had to be approved by 10 different Department of War officials. To add to this, the judgment sent to Roosevelt was that the book was, “decidedly objectionable,” and, “should not receive publication.” In the report it admits “the attacks on Indians were substantially confirmed, but should not be made public.” It also admits that the prisoners of war being held, including Geronimo, were lied to by the government in the peace treaty and that the captives were “treated poorly.” Still, to his credit, Roosevelt approved the publication. He did advise Barrette to disclaim his responsibility towards what was written, which he did.

This story was difficult for me to read. In doing research for this post, I listened again to the audio book to familiarize myself with the material. It had been a couple of years since I had read it the first time. As I listened, tears ran down my face in empathy.

Geronimo’s story is one of a man who wanted no more from his life but to live with his family and nature. He was a deeply religious man in the Apache religion that taught peace. In describing Yusen, the God of the Apache, he says “Yusen does not care for the petty quarrels of man.”

To show the honor of this great leader, Barrette says, shortly after agreeing to tell his story, Geronimo changed his mind and did not want to continue, but because he had promised, he finished. He was a man of his word. On one occasion the translator arrived without Geronimo. He explained that the old man had pneumonia and was running a high fever and would not be able to talk. Just then, the old warrior was seen riding in the snowstorm outside in subzero weather at full speed on his horse. When he came inside, he informed them that he promised to be there, and he keeps his promises. Seeing that he was in no condition to talk, after he warmed himself by the fire, they relieved him of his obligation that day and allowed him to return the 10 miles back to his house.

His journey into history started very modestly. Though a chief, his father died of natural causes when Geronimo was 17 years old. In his tribe at that age, he was a man. As a man, the responsibility of taking care of his mother fell to him. Besides this, he also was admitted into the council of warriors. Soon after this, he married. In the book he describes the pains his new wife took to decorate their home. They were happy. This joy led to three young children. It is telling that Geronimo calls this part of his life, “The times of freedom.”

It was the summer of 1858 and the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua tribe of the Apache were not only at peace with the neighboring tribes, but also with the neighboring government of Mexico. They had recently signed a peace treaty with the Mexicans. In this safe condition, Geronimo and many of the men went to trade.

While they were away, the Mexican Army attacked. When Geronimo and the other warriors returned home with provisions, the soldiers were still slaughtering the women and children of his village. They fought the invading army off. Geronimo’s mother, wife, and three young children lay dead before him. Fearing the return of a larger force, they had to leave their dead behind and seek a safe place to hide and regroup.

A vote was taken in the tribe, and it was decided that they would not go to war. They were severely outnumbered and desired peace. Even Geronimo, after the murder of his entire family, voted for peace.

This man was now in his words, “without a purpose.” When it was safe, he returned to his village and burned both his and his mother’s homes to the ground, including the beautiful decorations his wife had made. That day he vowed vengeance on the Mexican Government.

When he returned to his tribe, they had gathered an army from many neighboring tribes to fight off the invading Mexican Army, which had continued its advance into the tribe’s land. The invaders had continued to kill Apache everywhere. They voted for war.

Geronimo was named as leader of the effort because he had been wronged the most. Not only did he vow to lead, but he also vowed to be in the front. He wanted to be the first Apache to shed Mexican blood. In all, the Apache had 3 divisions. Geronimo knew the land and also acted as guide.

When they found the Mexican army, Geronimo started with a war cry. The battle lasted 2 hours. On the part of the field where Geronimo fought, it came down to just 4 Apache standing in a sea of dead Mexicans. As they prepared to leave, more Mexican troops came over the ridge killing the other three Apache. Geronimo continued to fight and eventually, he and the Apache were victorious. Geronimo was later named War Chief of all Apache.

In the aftermath of the battle he was able to identify the soldiers who had killed his family among the dead. Though he rejoiced in the avenging of their deaths, he said that he felt no less for their loss. He just wanted his family back. He wanted to look on his mother, hold his children, and love his wife.

After this battle, most of the Apache were satisfied. Geronimo was not. He began raiding into Mexico. He won and lost many small battles. In his raids he discovered that the Mexicans were taking women and children as slaves. This was barbaric to him. Apache did not kill non-combatants, but they did take prisoners. The men were never chained, but were watched over and made to work. As for women and children, they were treated as members of the tribe.

When he was asked about the supposed atrocities of the Apache, he said “The Apache received their education about so called, lawless raids, from the Mexicans and white men.” He continued with, “The example was set by your two Christian Nations, for the Apache.” Geronimo attested that the Mexicans and white men repeatedly murdered women and children. This Barrette corroborated from multiple sources, both that the Apache did not perform these actions and that their enemies did.

On a raid, Geronimo, sneaking close to a Mexican fort, heard the order given to the Mexican soldiers to kill every Apache man, woman, and child. Mexico, like so many other governments, officially ordered its soldiers to commit genocide. Mexico had the gall after this to call Geronimo, “The Red Devil.”

When the United States entered Apache territory, the Apache saw the U.S. as a possible ally in their fight against Mexico. After some time the United States Army asked the Apache to try to make peace with Mexico. They agreed, and shortly after, a peace treaty was signed. Unknown to them, the U.S. began tracking the Apache. Geronimo said that he considered white men, “good men.” He liked white people; however, he would come to despise their government. Once again, the Apache were at peace.

After some time, skirmishes arose between American Soldiers and bands of Apache. It was a practice of the Apache that when someone committed crimes, such as murder or rape, the convicted would be banished from the tribe. Sometimes, Geronimo said, these banished individuals would come together and attack both Apache and white men. He blamed these people for the attacks on the white men.

To resolve the tension, the United States Army set up talks with the Apache leaders. Geronimo had gone back to farming, so he did not attend. When the Apache leaders arrived in good faith for the talks, they were led together to a large tent in the center of a field. When all of them were inside the tent, the American soldiers opened fire on them in attempt to kill all their leaders. To the detriment of the government, some of these highly skilled warriors escaped. Geronimo joined in the plans for revenge. In this war council he said that the Apache should not make war on the white man. He continued that the oppressive force was the government and its soldiers and that the white men were not his enemy.

Geronimo would never trust the United States again. They sent spies into the forts as guides. Still, hostilities continued. A great chief had arisen that united all of the Apache. His name was Mangus Colorado. Seeing that the tribes were uniting against them, the soldiers sent word of a peace treaty.

In the conditions of the treaty, it said that the Indians would be allowed access to provisions of food and supplies, and in exchange, they would live close to the fort where it could be assured that they were not on the war path. The government told them that the last event was a mistake, and that they could trust them to make it right. In the plan, all of the Apache would be moved to the new settlement.

In council, Geronimo opposed this plan; he felt it was just another trick. The compromise was that Mangus Colorado would lead half the tribe to live with the Americans. He would take most of the weapons and horses with him to ensure they were “safe.” Colorado said that he was happy to finally make peace with these honest men. Geronimo would stay behind to lead the others and then join their brethren after a little time has passed. Mangus Colorado and half the Apache population were never heard from again.

Fearing an attack, Geronimo and the rest of the tribe fled. On their retreat the American Calvary attacked. The Apache were severely defeated because they had few horses and even fewer guns. They fought with spears and bows and arrows. What was left of their horses were either killed or captured. Geronimo continued to retreat. Ten days later they were attacked again. This time the Apache were down to rocks and clubs as weapons.

Regrouping, Geronimo was elected leader of what little was left. They hid for a year before being attacked again right before winter. The Americans took all their supplies. During the winter the government sent envoys to Geronimo offering food and supplies, he refused them. He sought out help from other tribes and received it.

After a long, hard winter, finally a soldier named General Howard came himself to Geronimo offering peace. Reluctantly, he agreed. Believe it or not, the officer kept his promise. Geronimo said of Howard, “We never had as good a friend among the United States government as General Howard. If there is only one honest white man in the United States Army, that man is General Howard.” Unfortunately, he would be replaced.

Soon after, the tribe disbanded, figuring it was a new time of peace. Geronimo took his people to New Mexico and away from the fort called “Apache Pass.” He saw the unrest occurring between the different bands of Apache at the fort and did not want to fight his own people. He also knew that if the white men saw the infighting, they would use it as an excuse to clamp down on them.

While peacefully living in New Mexico, he received word that his “friends” in the U.S. government wanted to meet with him. He took one of his closest allies with him and met with them. They immediately disarmed the Natives and captured them. Taking the two Apaches back to the fort, Geronimo was put in chains. He was then tried. They released the other Apache. When Geronimo asked why he was taken, they responded with, “You left Apache Pass.” He was never told that he was to remain there, but now, he was being held for leaving. So much for the freedom of movement. He was kept for 4 months and tried again. He was not allowed at this trial, but he was released.

Returning to his people, he lived for two years in peace. They began hearing rumors that the American government was planning to capture and imprison the Apache leaders. They were also told that there was another “tent” waiting for them. Feeling that it was “more manly to be killed on the war path than in prison like Mangus Colorado,” the Apache attacked. This caused the soldiers to retreat.

Another year of peace passed. A new general, they found out, had taken command. His apt name was General Crook. Crook ordered his soldiers to round up all Apache horses, cattle, and most importantly, to capture or kill the “Red Devil,” Geronimo.

They fled to Mexico with 400 men. United States troops followed, taking women and children captive. While escaping the Americans, they were ambushed by Mexican soldiers. It was discovered that Mexico and the United States were working together. The two nations had 2000 soldiers ready to exterminate the 400 Apache warriors.

Crook set up a meeting with Geronimo. In this meeting Geronimo was asked why he left the reservation and fled into Mexico. He answered, “You told your soldiers to put me in prison and if I resisted to kill me. If I had been left alone, I would have been in good circumstances, but instead you and the Mexicans are hunting me.” Crook assured him that the rumors were untrue. Geronimo did not believe Crooks, but wanted peace, so he returned with him.

In official Army documents that have been released, it outlines that the rumors were not untrue. Crook had issued those orders. Crook took most of the tribe back into the United States. Geronimo worried about treachery and fled with the warriors into the mountains and disbanded into small groups.

Geronimo attacked using guerilla warfare tactics on the Mexicans who still were hunting him. After taking heavy losses, the Mexican government signed a peace treaty. In the talks, Geronimo learned that the U.S. had initiated the cooperation with Mexico to exterminate the Apache. As part of the treaty, Geronimo left Mexico.

Seeking peace, Geronimo sought out another General named Miles. He conveyed to Miles that he wanted peace and reconciliation with his tribe. In their meeting Miles told him that his president, Roosevelt, wanted peace as well. Miles performed a ritual with a rock that Geronimo saw as sacred and swore an oath that the U.S. and the Apache were now brothers. He took the sand and pushed it aside saying that this represented all the past troubles being cast away. Geronimo did not trust General Miles but did trust the president and the ritual.

In the treaty, Geronimo was promised that he would be taken care of from now on. He was told that he would never have to work again. Miles promised him that he would see his people who had been sent to Florida in 5 days. His response was, “sounds like a story to me.” Miles told him, “While I am alive, you will not be arrested.” In response Geronimo promised to never return to the war path or attack Americans again. Geronimo in retrospect said, “I don’t believe I ever violated that treaty.”

Before this meeting, in February 1887, the senate passed a resolution. It, and the dispatches connected to it, show that Miles was ordered to capture or kill all hostile Apache. It proves that the United States government did reach out to Mexico to perform genocide on the Apache.

The “peace treaty” that Geronimo signed was not a treaty, but an unconditional surrender; so much for brotherhood, and Geronimo living his days happy, without work. The surrender made Geronimo and his band prisoners of war. In Miles’s report, he admits to misleading Geronimo. He also admits to the Army’s murder of Mangus Colorado and his people. All evidence sides with Geronimo. Also included in the account by Barrette were multiple corroborating accounts.

After the surrender, Geronimo was put in a labor camp in Alabama, where he was forced to work in a saw mill for 2 years. He never made it to Florida. In a Washington post article, it describes the horrible condition in Alabama and says, “The Apache in Alabama die like flies at frost time.” Geronimo was held as a prisoner of war for 20 years. Eventually, he was allowed some animals to raise and feed himself. The Army was caught embezzling money that was supposed to go to the upkeep of the camp that held Geronimo and his people.

All Geronimo wanted in his later years was to return to Arizona. He believed that his god put tribes of people in certain places, and those places were sacred to them. His home was not Oklahoma.

The government continued to fail to uphold their side of the agreement. He realized that he would die in bondage. The government paraded him around at the world’s fair. This once proud warrior only agreed to go because he was given money that he desperately needed.

In the winter of 1909, while riding his horse back home, Geronimo was thrown onto the ground. He was injured and had to lie outside in the cold weather all night. He would be found half dead. Suffering, now from pneumonia, he soon died. On his deathbed, he confessed to his nephew that he regretted surrendering. He said, “I should never have surrendered, I should have fought until I was the last man alive.” His last request of his government captors was to be buried in Arizona near his father’s grave. He is buried in Oklahoma.

As a final slap in the face to this honorable man, the members of the elite club for students at Yale University, Skull and Bones, stole Geronimo’s skull and use it in their initiation ritual. This club, whose members include people like George W. Bush and John Kerry, is composed of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world. Their influence on politics, banking, and business is undeniable. What other reason could they have to use his skull than to symbolize their power over those who oppose them?

In this series, I have discussed freedom fighters from a variety of angles. This one hits especially hard. It is enjoyable for me to talk about and bring to light less recognized people who, in their particular way, fought for liberty. This one is different. With heroes like Thomas Young, they fought the good fight, and though they might have been pushed into the backroom of history for one reason or another, they were victorious. Geronimo lost. He failed to set his people free. There are fewer than 200 thousand Apache left. They are spread from northern Mexico through, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and parts of Texas. They are a broken people.

It is important for those of us in the Freedom Movement to not only recognize when we win, but also when we lose. We can learn from Geronimo. He lost because his fight was kept from the public. The lies that the government spread about his people were not challenged. We must learn to stand in a peaceful way and defend ourselves from false allegations. The corruptions in government must be exposed and used to sway public opinion using the truth. The institutions of government must be shown to be exactly what they are, violent and unethical. Only then will the people of the world stand in one voice and upraise the individual in personal ownership.

Some, who always apologize for the offenses of government, will say this was over a hundred years ago. They will say we made mistakes and those mistakes have been corrected. Really? This story reminds me of what is going on in Syria right now. “Mexico” is the Syrian government or the Russian one. This country is still the one committing war crimes. The United States is still building an empire. It still invades, just like the US conquered the land that belonged to the Apache. It is simply not in this country alone, it is in the Middle East in countries like Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan. This Apache story of lies, deceit and tyranny plays itself out all over the globe in Yemen, Chechnya, The Ukraine, and Haiti. How many tribal leaders has this government, or any other government, lied to, cheated, or stolen from today. This is what unethical people do.

This story recalls the statements that Adam Kokesh, and others, have made about our foreign invasions. They, rightly, say that we are making enemies faster than we can kill them. Adam is also right when he says that the enemies of freedom are not to be found in far off lands, but right here.

It is time for us to cause the violent monopoly of force and slavery to be driven from this world. It is time for all of humanity to push aside the chains of governance. I will not make the mistake that Geronimo made. I will not surrender, I will not sit down. Most importantly I will not shut up. We will win this fight and we will do it with peace, with truth, and with Love.

In the name of Geronimo consider this MY oath.

Written by @marcus.pulis

Sources

My Life: The Autobiography of Geronimo by Geronimo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geronimo

Categories: Politics